Author: Andy Mukherjee

India’s dominance in technology outsourcing faces an existential challenge similar to that fought – and lost – by its world-leading textile industry 300 years ago.

In the early 18th century, spinning 100 pounds of cotton took 50,000 hours. “Indian spinners were considered the most productive in the world and produced the highest quality products,” note Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson, economists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in a novel paper. However, by 1795, automation reduced the demand for labor to 300 person-hours.

The industrial revolution’s profound impact on cotton spinning could be replicated in a $250 billion white-collar company. Every year, 5 million Indians create billions of lines of code for global banks, manufacturers and retailers. Research conducted by McKinsey & Co. showed last year that generative AI could reduce code generation time by 35-45% and cut documentation time by almost half.

This is just the beginning. As generative AI evolves into artificial general intelligence – machines that rival human cognitive abilities – even highly intricate tasks may not require experienced programmers.

Speed improvements “can be translated into productivity gains that outpace previous advances in engineering productivity, driven by both novel tools and processes,” McKinsey says. But how will the profits be distributed between customers and software providers? More importantly, how will they be distributed between the outsourcing companies’ shareholders and their employees?

Acemoglu and Johnson gather insights into the interplay of machines and work, comparing the age of artificial intelligence with the early industrial revolution and the change it wrought in the thinking of David Ricardo, the eminent classical economist, prominent bond trader and politician. As Jenny’s mill became more and more competent, suddenly there were plenty of yarns looking for weavers, creating novel, lucrative jobs. MIT economists speculate that the golden age of weaving probably occurred when Ricardo famously concluded that “machines did not reduce the demand for labor.”

When hand weaving gave way to power looms in the early 19th century, leaving no alternative employment for displaced workers, Ricardo updated his view. In an 1819 speech before the British Parliament, he admitted that “the inadequacy of wages to support the working class” was one of the “two great evils for which it was desirable to provide a remedy.”

Indian tech companies are stuck on Ricardo 1.0 and investing very little in a future where AI has made their current code-writing business irrelevant. The bullish view is this: Someone needs to ask the right questions of the vast language models of generative AI. Natural language processing and rapid engineering will create jobs. Finding unique and affordable operate cases — especially in local languages — could be another way for the world’s most populous nation to leverage its talents.

According to Nandan Nilekani, co-founder and CEO of Infosys Ltd., India’s second-largest outsourcing company, building basic AI models is for people with capital. “Our advantage today is not compute(1), cloud or chip,” he said in the speech. “Our advantage is the population and its aspirations.”

The problem is that the AI will come with its own power loom. Companies will recoup huge investment costs by selling improved devices. “We expect AI-enabled hardware to be the only sustainable and meaningful way for consumers and corporations to start paying for AI features, justifying the billions of dollars invested in GenAI,” writes Nilesh Jasani of GenInnov, a global innovation fund based in Singapore.

Computers, phones and tablets that stay ahead of the curve can control access to the smartest teachers and navigators, the best office assistants and the most empathetic robotic friends. To extract value from this novel world, Indian outsourcing companies may have no choice but to emulate the transformation at Alphabet Inc. and Microsoft Corp.

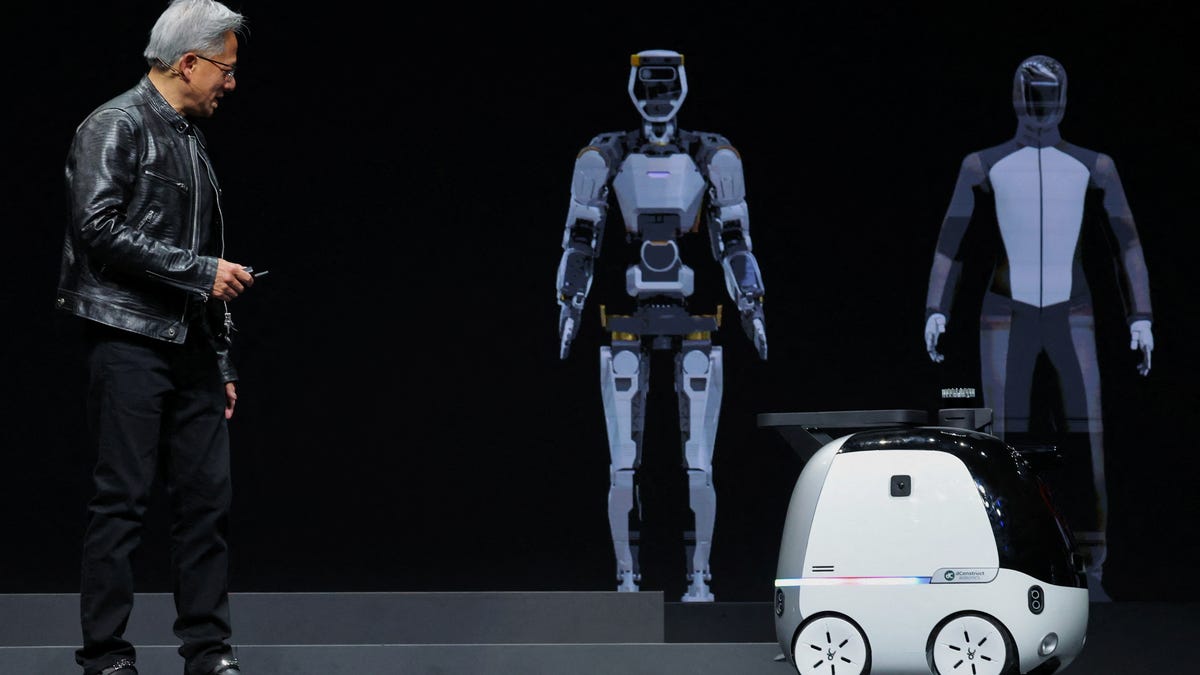

Ten years ago, these software giants saw no need to invest the truckloads of money that routinely flowed in from advertising or subscriptions. But they turned their attention to Nvidia Corp., which has become the world’s most valuable chipmaker by enabling the artificial intelligence revolution: “Artificial intelligence is eating software,” Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang said in 2017. Currently, Alphabet and Microsoft have committed to using one-third of their operating cash for capital expenditures.

Infosys and its larger rival Tata Consultancy Services Ltd. appear to have ignored the memo. The billionaire founders of Indian outsourcing companies are admired by the public because of all the jobs and wealth they helped create. Why would they gamble all this on a risky long shot?

Ultimately, however, shareholders’ pursuit of high dividends and liberal share buybacks may threaten the future of newborn engineers. India’s vaunted institutes of technology were unable to fill all their graduates this year. For the first time in over a quarter of a century, the outsourcing industry in the country is shrinking.

Some of the economic downturn may be cyclical. But what if part of the decline is due to artificial intelligence, reflecting Ricardo’s concerns about the textile industry? And he was right – real wages for handloom weavers fell between 1800 and the early 1820s. “We found little evidence that increases in employment or wages can be offset in other industries,” the MIT economists note.

It’s not too behind schedule for a twist. There are plenty of resources available. The Biden administration is awarding billions of dollars in grants and loans to Samsung Electronics Co. and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. for chips that will be used in artificial intelligence. Elon Musk’s XAI just raised $6 billion to challenge OpenAI. Closer to home, the economic rivalry between MBS and MBZ – Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and UAE President Mohammed Bin Zayed Al Nahyan – is a wishing tree that Indian entrepreneurs should shake vigorously. Unfortunately, reputable outsourcing companies do not realize this.

Andy Mukherjee is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial and financial services companies in Asia.

Most read on the Internet